I, Lycanthrope

Werewolf Physiology – Separating Fact From Fiction

If you were to travel the world today asking people what a Werewolf looks like – using local nomenclature as appropriate of course – you would get hundreds of different answers. This result may strike you as peculiar, seeing as almost every society on Earth, for tens of

However, as with most phenomena which achieve an air of myth, local color and circumstance have a way of irrevocably infecting people’s perception of reality. Over the course of history, around the wide world, these local details and quirks have transformed the Werewolf into a wide variety of strange beasts.1

Here we will attempt to understand the ways in which Fact and Fiction intertwine to define the Werewolf – or Werewolf-like creature – in the public imagination.

One of the earliest written references to Werewolves can be found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, written over 2000 years ago. Depicted to the left by Dutch artist Hendrik Goltzius, Ovid tells of how King Lycaon attempted to trick Zeus into eating the meat of Lycaon’s own dead son. As punishment for this foul deed, Ovid writes that Zeus cursed Lycoan, turning him and his remaining offspring into a wolf.

In Goltzius’s imagining of this story, Lycoan takes on a predominantly human form, albeit with the addition of a fairly benign

However, despite the artistic liberties taken by Goltzius, Ovid’s recounting of Lycoan’s transformation is almost certainly a thinly veiled mythical explanation for a very real biological phenomenon. It almost certainly relates back to a ceremony referened in Plato’s Republic centuries earlier, the Lycaea, which involved ritualized cannibalism and the purported transformation of human beings into wolves during the worship of Zeus.

In the modern age, we now know that neither Gods nor magic has anything to do with Lycanthropy. Whereas the Lycaea ceremony was for centuries considered a pagan ritual, it’s reality was likely far more practical: that is, the ritualized feeding of a local pack of Werewolves in order to sate their blood-lust. Under these auspices the Lycaea ceremony has lived on throughout history, even into the modern age – though under many other names – as local peoples attempt to navigate the morass of Lycanthropic relations.2

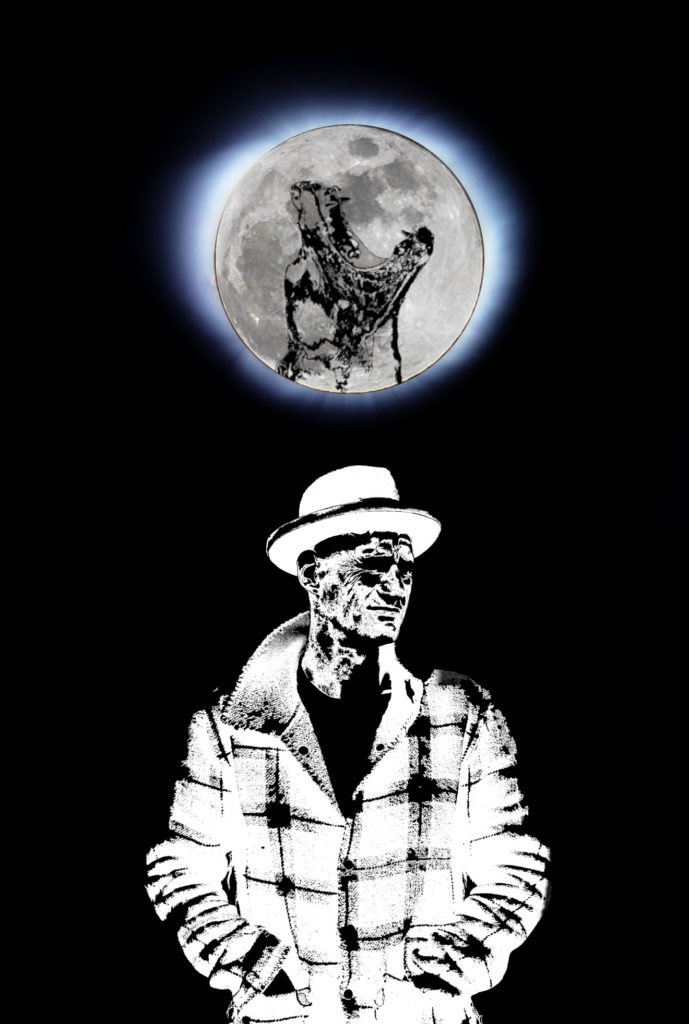

Although Ovid’s writing was the first concrete description of Lycanthropic infection, Goltzius was not the first to depict a werewolf illustration. That honor, as far as the surviving artistic record is concerned, falls upon Cranach The Elder, who crafted the wood-cut print to the left in 1512.

Perhaps in order to avoid depicting the horrible reality of Lycanthropic infection in its awful fullness, Cranach the Elder all but eliminated the “wolf” from the visual depiction of the Werewolf. Indeed, there is little in this image to differentiate the Werewolf devouring a human child from a particularly violent mad-man. Our only visual clues are the slight elongation of the right foot and fingers of the left hand taken together with the killer’s prostrate position on all fours.

With Cranach the Elder’s

Over many years European artists slowly brought their illustrations closer in line with reality. Consider, for example, 100 years after Goltzius, and almost two full centuries after Cranach the Elder, the 1685 illustration to the right. Observe the werewolf form hanging on the gibbet bears not only the

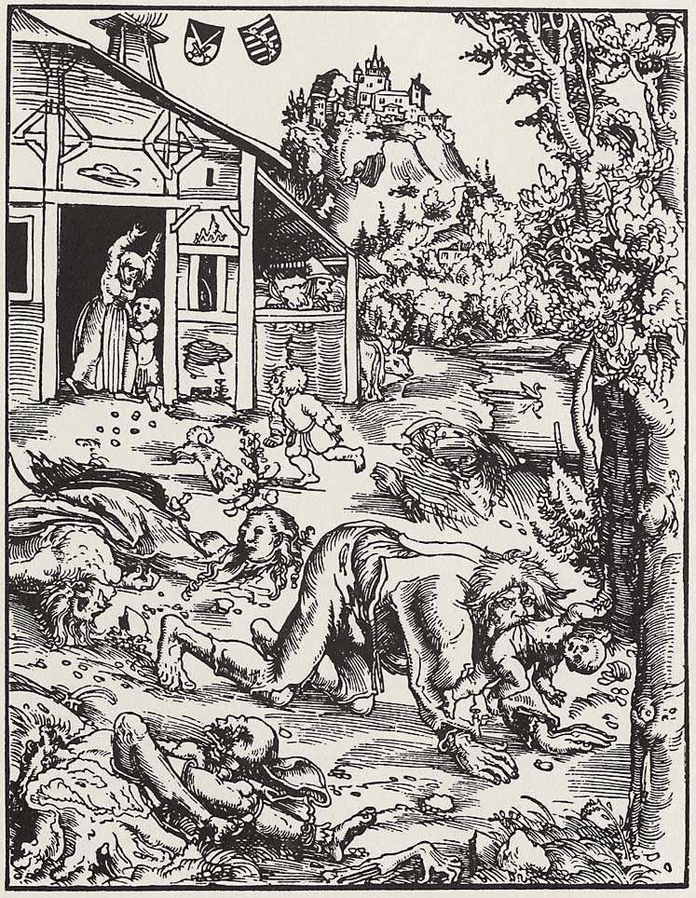

Another depiction, around the same time, is the first to dare show the entire, completed Lycanthropic transformation. The werewolf to the left still retains the tattered remnants of its human clothing, even as all of its once human features have been obliterated.

An image such as this would have been hugely controversial in its day, despite being quite tame by modern standards. It was not until the 20th century that the Werewolf became a visual exploration of the Lycanthrope was explored in earnest.3

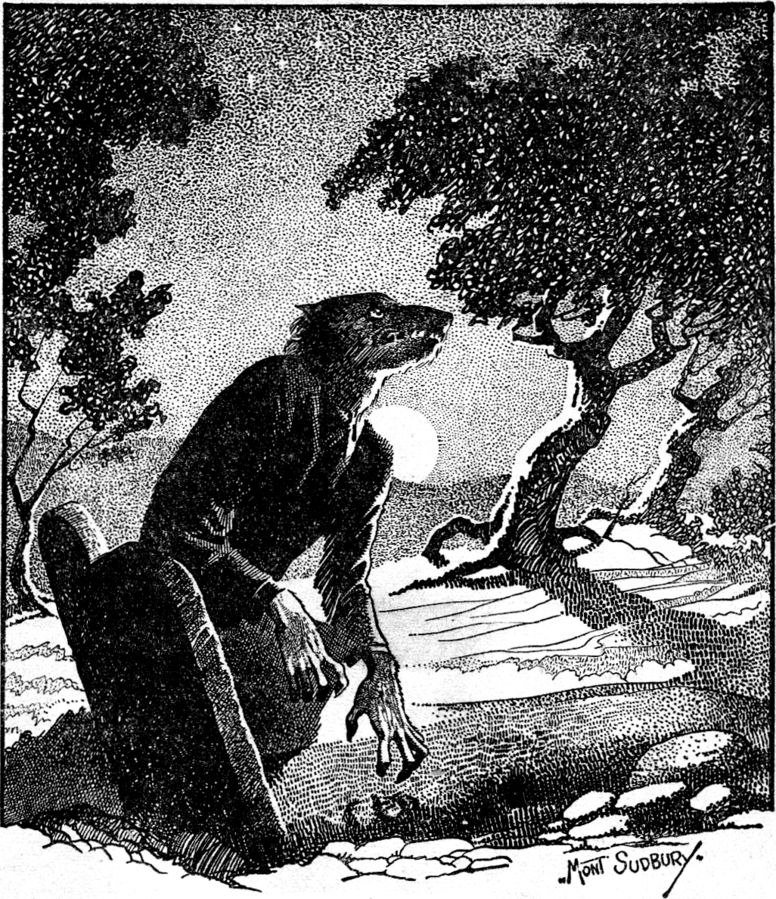

By the 1940s, werewolves were not only depicted with relative accuracy and fullness, but stories involving werewolves were being freely told in both illustrated comic books and pulp fictions.

Consider this prime example to the left from the Pulp magazine “Weird Tales,” illustrated for an accompanying story entitled “The Werewolf Howls.” Mr. Sudbury is clearly familiar with Werewolf physiology and, though he does humanize the depicted figure with the inaccurate retention of human clothes, the elongated curling of the sharp taloned fingers and unequivocal canine skull structure do not shy away from Lycanthropic reality.

1940 can fairly be considered the beginning of a renaissance in the depiction of Werewolves, to be sure. But even as Lycanthropes normalized in the artist’s workrooms and the public eye, still it is not until the late 21st century that true physiologically accurate depictions began to appear. Like the absurd “

It was not until 1981 that a near perfect visual rendition of the Lycanthropic form was at last depicted in a widely dispersed media. I am, of course, referring to John Landis’s biopic masterwork An American Werewolf In London.

I do not know Mr. Landis, nor can I speak to his personal experience with Lycanthropy. However, I am not alone in the Lycanthropic community when I say that An American Werewolf In London features, to this day, the most accurate single depiction of a Werewolf’s transformation in the history not only of

I still remember seeing the film for the first time. The Transformation scene is so accurate in its unwavering devotion to

Whoever worked with Mr. Landis on this film had an intimate knowledge of the Lycanthropic experience, and I commend both them and Mr. Landis for their courage in shedding a stark light on such a taboo topic.

I have included the scene embedded below. Although watching it will give the reader an excellent idea of the dramatic and torturous nature of the Transformation, as well as the final Lycanthropic form, I must also warn you, it is not for the faint of heart.

Here, at last, fiction and fact all but collide. In the years since 1981, depictions of werewolves in mass media have increased steadily, as have their relative accuracy and, as a result, their ferocity. Nowadays it is not at all uncommon for even a middling special effects studio to produce nearly photo-realistic depictions of Lycanthropes in the throes of their

This is not to say that modern depictions of Lycanthropes are wholly accurate. Far from it. We have already dealt with several misconceptions up to this point in the book, however, next chapter we will delve into one of the most confusing and contradictory of topics – one rife with inaccuracies which not only offend academics in their ivory towers but which have also gotten many well-meaning people killed – the abilities and weaknesses of the Lycanthrope.

1.For proof of the ways in which the vagueries of local culture can run amok with the truth, look no further than the widespread belief not in Werewolves, but rather “Werecats“. The image to the left, from the mid-1700s, provides as good an illustration of this totally fictitious creature as one could ask for. However, it should come as no surprise to the reader that the transmogrification of the reality of the Lycanthrope into the outright falsehood of the “Werecat” has its primary locus in certain parts of the African and Asian continents – areas of the world where, historically, there are no significant natural populations of wolves. Instead, the peoples of these areas would have suffered under the constant threat of large, predator cats. Hence the development of the “Werecat”, along with its fellows, the “Weretiger” and “Werelion.” Faced with an irrational horror, it is human nature to assign it the most fearsome known face, and historically that face changes from country to country and sometimes even town to town.

2. It should be noted, that although no earlier document describing werewolves has survived the chaos of history, this is almost certainly the result of sheer chance rather than a lack of Lycanthropic infection. Indeed, the question of whether Werewolves predate even Plato and the Ancient Greeks has been solved beyond all doubt. Archeologists in a cave system in the south of France have found the remains of an entire clan of Lycanthropes, manifesting as a series of skeletons neither wholly animal nor wholly human. Carbon dating has traced these remains as far back as 40,000 years.

3. It is not a coincidence that the 20th century brought with it a sudden willingness of artists and the public to create and enjoy unflinching depictions of Werewolves. Due to a confluence of developments in modern weaponry, social structures, and scientific knowledge, the first half of the 20th century saw a steep decline in the relative danger posed by Werewolves and marked the beginning of the steady decline in Werewolf numbers which continues to this day. It was only this reduction in the danger posed by Werewolves which allowed modern peoples to loosen up and view Lycanthropes plainly, or even as objects of popular entertainment. Up until this point, the majority of people can be forgiven for not wanting to make light of a creature which might, on any given full moon, devour them or their

4. The assiduous reader will no doubt comment – ‘but the entire scene spans only two minutes, and you’ve just said

If you’ve enjoyed reading this or any of my hundreds of other stories – if they’ve made you laugh or cry – if they’ve excited you or got you thinking – if they’ve stimulated your imagination in a pleasurable way – then please consider supporting me financially on Patreon. As a burgeoning author, even a dollar a month means a lot!

CLICK A GENRE TO CONTINUE READING A RANDOM FLASH FICTION IN THAT GENRE

| Action | Apocalyptic | Dark |

| Established Universe | Fantasy | Funny |

| Misc | Science Fiction | Science Fantasy |

| WTF Is This? | Random Any Genre |

READ LONGER STORIES

| THE DEMON’S CANTOS | INCIDENTAL SUPERHERO |

| BENEATH | THE HUMANITY SAGA |

| THE TRAVELER | I, LYCANTHROPE |